Capitalist poetry is produced by its advertising industry and its marketing teams. Its poetry can be understood as deeply rooted in racism. This essay focuses on one example of capitalist poetry that can be understood as racist. The title of the poetry is Kentucky Fried Chicken. Futurists might have enjoyed my interpretation of the poem. One doesn’t need to look far for other examples of capitalist poetry. It is all around us 24/7. However, there are examples of capitalist poetry that are also racist. While some people who voted for Obama have earlier labeled the era as the first “post-race” era, or congratulating themselves for being progressive, the capitalist poetry that is also racist is being experienced by and performed by people who know that they are involved with the art. To be certain, many other people performing capitalist poetry don’t know that their acting (in ironic guerrilla fashion) on the enticements from a marketing campaign and that acting on such enticements is performing support for racist poetry and products because they are lending support with feet, dollars and bellies as they might a gallery or buying a “cutting-edge” book of poems. In fact, they are performing the poem. Capitalist poetry is poetry which holds the sublime experience as one of exploitation. It drives our consumer culture by way of marketing teams’ advertisements of products. The art of exploitation manipulates an audience into spending money, giving it, not a traditional sublime experience, but an experience of exploitation and of oppression in place of the sublime that also encourages the audience’s/customer's/victim's return for more. The Dalai Lama calls this strategy one of providing the potential customer a sense of “confusion, attraction, and aversion.” The beginning of every ad is one of distraction, confusing the potential purchaser. The attraction moves the potential customer to the product for purchasing. The aversion that the purchaser experiences is one that the Dalai Lama describes is one of giving a thirsty man a glass of saltwater. The purchaser may be convinced by the marketing that the customer is in for a sublime experience when in reality he is short-changed, is victim to flim-flam. The marketing firm, seller, and producer wear the smile.

0 Comments

During the first semester of my first academic year at VCU, my FI 111 classes used the concepts in Paulo Freire’s essay “The Banking Concept of Education” (Ways of reading, 256-271). The class used Freire’s idea of oppression when looking at the world by way of national historic documents and international news via newspapers. The second semester of FI (112), the students and I explored the early feminist ideas of Marilyn Frye (“Opression,”1983) and Simone de Beauvoir “from Second Sex” (Jacobus A world of ideas, p.173-185). I used basic feminist thought because I had a personal interest in the movement, having been revising a collection of poems that worked with feminist ideas. Second semester we got familiar with the notion of the sublimes and discovered connections between masculine and feminine sublime. Indeed, while the masculine sublime attempts to overwhelm one with experience, we found in de Beauvoir’s “feminine mystery” (p.179) Jean-François Lyotard’s “feminine sublime” (as cited in Freeman, 1997, p.162). In FI 112, the same lenses/concepts/themes are used and given definitions as a member of an academic discipline might use. My hope was that the lenses became language for students to use in discussions and on papers and that the connections between Freire’s notion of oppression and de Beauvoir’s feminine mystery would be made. Concepts are chosen to suit my interests for my research and writing, but of course they must be able to be found by students. Having concepts that I am interested in is important so that students intuit my interest. So I try to choose concepts that seem rudimentary or banal but are able to reveal interesting notions with closer scrutiny. I have taught upper-level courses for several years and am aware of what one might expect from freshmen. During the second semester, we built on what we examined first semester, reading The Dew Breaker (2005) and watching “Thelma and Louise” (1991). Students found themselves examining the difference between Modernism and Postmodernism via masculine and feminine sublime. To be certain that students understand the concepts and their contexts, they perform close reading of an essay that contains or better yet defines the concept. Students are going to read the essay at least twice under my supervision and then write a paper on it or take an essay exam. (The reading, journaling, and demonstrative writing here is transparent so students may model it in other courses that may have difficult readings.) Appendix B is an example of class times during the reading, journaling, and writing using the sequential and spiral curriculum. Appendix C includes the fall FI 112 semester schedule. However, though the sequential and spiral curriculum is modeled here, the particular lesson is for the reading of Paulo Freire and continues toward a paper on his concept. from The International Journal of Critical Pedagogy http://libjournal.uncg.edu/ijcp/article/view/297/852 My poetry is postmodern with a connection to Hopkins. For the last decade or so the work has had a growing number of aversions. To date it has aversions to direct objects, "I," "of” and possessives, the verb to be, and similes. My personal manifesto for this period of my life may be articulated as follows.

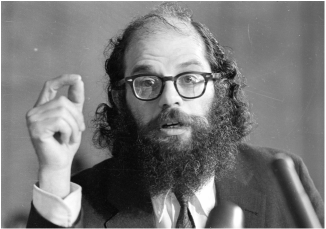

In order for a privileged person to appreciate anything, there is a move toward the margins. For the poet, this means removing oneself as best as one can from the mainstream ideology or culture whose thinking is one of embracing the convenient answers to questions, allowing oneself unconsciously to be led, allowing the “experts” to answer for one. By doing so, the collective consciousness eases language fluent or fluid so that platitudes, clichés, and group-think create for us. By moving toward the margins, the poet is moving to the periphery of the symbolic order also. I am convinced that it is at the margins where one finds possibility, not in worn-out phrases and ideas. If nothing else one finds a starting point for an opposing strategy and perhaps a new language for describing and contemplating the plight of thinking for oneself instead of mainstream ideology, that is after all pop culture. Ginsberg’s Performativity: Stumbling Blocks and Points of Resistance (from unpublished longer essay)11/18/2015  It is Part III of “Howl” where its language is performative. “Carl Solomon! I am with you in Rockland / where you are madder than I am” is performative in its empathic gesture, its solidarity with a man in an asylum. (24) The performance is persistent in its stating “I am with you in Rockland” 18 more times in the poem. (24) The performance seems one of giving legitimacy to those considered to be insane, outside mainstream ideology nearly outside power and knowledge. Ginsberg then is using his role as a poet, a troubadour, and “legislator of the world” to call attention to the plight of the homosexual, the institutionalized, the anti-capitalists, and the marginalized populations and to legitimize them as humans struggling as workers. Thus his reference to “The Internationale:” Here again the military/militant imagery echoes. If the poem’s inversion (of heaven and hell) wasn’t clear in the three parts, the Footnote makes it clear that the “bum’s as holy as the seraphim,” as is the “asshole,” “typewriter,” and “the vast lamb of the middleclass!” (27-28) Again, without regard for decorum and mainstream ideology, in an attempt to break alliance for the reader, the poet is “after the poem as discovered in the mind and in the process of writing it out on the page as notes, transcriptions.” (31) I suppose if Ginsberg was attempting to revive the poet as visionary prophet and attempting to produce a vision, this strategy may be one road to try, but the poem reaches back to religious symbols. Ginsberg’s groundbreaking poem was three years prior to Robert Lowell’s Life Studies. However, in my opinion, Ginsberg finds greater success and influences many more people than those who read poetry (though “Howl” certainly is a part) is the performance of his life. Ginsberg was unapologetic, irreverent of power structures, and reminded readers of Whitman’s dream of a more open America. Ginsberg recognized that “silence and secrecy are the shelter of power.” (Foucault 101) It is in the poem’s and Ginsberg’s acting out, the lack of decorum in life (and art) that creates “a stumbling block, a point of resistance and a starting point for an opposing strategy” that with a few other brave and vocal provocateurs created a counter-culture. (Foucault 101) One thinks of fellow spokes people of the day. In fact, it is the poem’s repeated speech act “I am with you in Rockland” that is the leaping off point to his life’s work and persona after “Howl” until he was in his sixties, when Reagan and Thatcher seemed to had the last word. Many readers have mentioned how “Howl” lacks decorum or how it “deliberately assaults and inverts it readers’ assumptions about what is holy or hellish, sane or mad.” (Gates 161) Here an understanding of “acting out” will be useful in order to understand the poem as a performance. Acting out, when deliberately used by psychologists on a patient to re-enact or to practice new behavior, can be seen as helpful and have positive results for the doctor and perhaps the patient who may wish to achieve general alliance with his society. However, acting out is in a general sense categories of specific behaviors that allow the professional and the conformed adult to label someone who is acting out of character, usually to manipulate the behavior to conform it and the person performing the behavior. Goffman defines conforming as the following:

“When an actor takes on an established social role, usually he finds that the particular front has already been established for it. Whether his acquisition of the role was primarily motivated by a desire to perform the given task or by a desire to maintain the corresponding front, the actor will find that he must do both.” (7) In fact, Ginsberg’s father had suggested to Allen, “[you have] developed intellectually; but, emotionally, you lag,” and in light that the poem is personal (confessional) and has often been called a rant, the term acting out may serve me. (Breslin 411) I am using the concept such as it is for the performance of his poem and for the performance of his life. Whether Ginsberg lagged emotionally or not, he created a new shape to a “social front” as Goffman would say. (26) He added depth to a bohemian front and merged it with those marginalized by way of their madness, drug use, homosexuality, and opposition to capitalism. With a handful of other spokespeople performing similarly at that time, he created a counter-culture, a culture that opposed mainstream culture for nearly 20 years. Acting out is always a spectacle in the minds of adults whose minds have conformed to state and mainstream ideology and perhaps now even having a great stake in their conformity. Acting out may be seen as a kind of graffiti, graphic by nature, making it “unpresentable” in the eyes of those who have conformed, the middleclass occupant with lots to lose. The poem itself may have been a written form of acting out that Ginsberg continued in his public performances for many years. Richard Elman reminds us that “his acting out became a way of perceiving his adversity and, through genius, overcoming it.” (329) In any case, the poem’s and Ginsberg’s performance of “genuine suffering” would be one on the fringe of symbolic order that makes up the primary code of mainstream ideology, creating disorientation, aporia. (31) |

Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed